Inside the ELF: ELF Header

A breakdown of the ELF header: its fields, their purpose, and how they define the structure of every ELF binary.

ELF (Executable and Linkable Format)

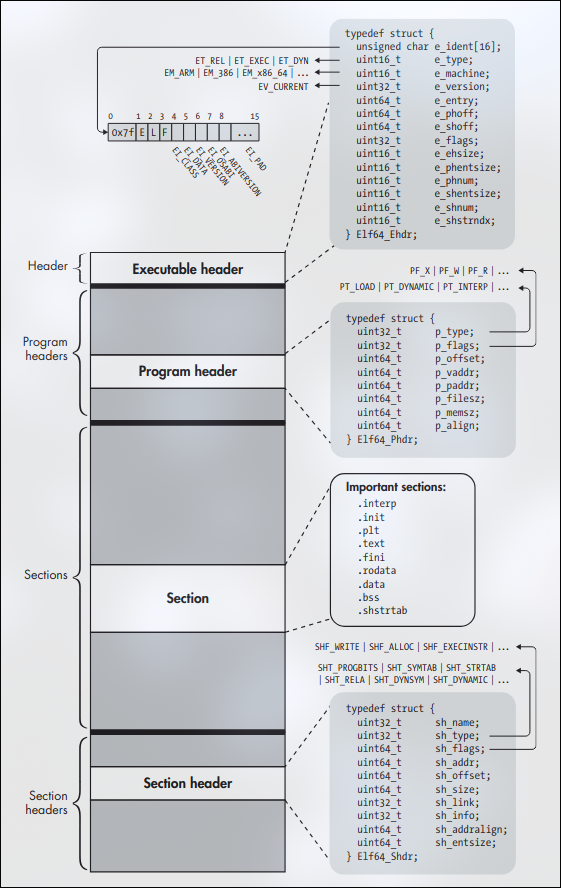

ELF is used for executable files, object files, shared libraries and core dumps in Linux. ELF binaries consist of only four types of components:

- Executable Header (ELF Header)

- Program Headers (Optional)

- Number of Sections

- Section Headers, one per Section (Optional)

As you can see in above image, the executable header comes first in standard ELF binaries, the program headers come next, and the sections and section headers come last.

In this blog, we are going to focus on the first part, i.e, ELF Header for 64 bit binaries.

Executable Header (ELF Header)

Every ELF file starts with an executable header, which is just a structured series of bytes telling you that it’s an ELF File, what kind of ELF file it is, and where in the file to find all the other contents.

If you’re interested in looking up the type definitons of ELF related types and constants, you can look up this path in your Linux system.

/usr/include/elf.h

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

typedef struct

{

unsigned char e_ident[EI_NIDENT]; /* Magic number and other info */

Elf64_Half e_type; /* Object file type */

Elf64_Half e_machine; /* Architecture */

Elf64_Word e_version; /* Object file version */

Elf64_Addr e_entry; /* Entry point virtual address */

Elf64_Off e_phoff; /* Program header table file offset */

Elf64_Off e_shoff; /* Section header table file offset */

Elf64_Word e_flags; /* Processor-specific flags */

Elf64_Half e_ehsize; /* ELF header size in bytes */

Elf64_Half e_phentsize; /* Program header table entry size */

Elf64_Half e_phnum; /* Program header table entry count */

Elf64_Half e_shentsize; /* Section header table entry size */

Elf64_Half e_shnum; /* Section header table entry count */

Elf64_Half e_shstrndx; /* Section header string table index */

} Elf64_Ehdr;

Definition of ELF64_Ehdr in /usr/include/elf.h

The executable header is represented here as a C struct called Elf64_Ehdr. You can notice that the struct definiton here contains types such as Elf64_Half, Elf64_Off etc. These are just typedefs for the following integer types:

- Elf64_Half = uint16_t

- Elf64_Word = uint32_t

- Elf64_Addr = uint64_t

- Elf64_Off = uint64_t

The e_ident Array

The ELF Header always starts with a 16-byte array called e_ident.

The e_ident array always starts with a 4-byte “magic value” identifying the file as ELF binary. The magic value consists of the hexadecimal number 0x7f, followed by the ASCII characters codes for E, L, and F. Having these bytes right at the start is convenient because it allows utilities and specialized tools such as binary loaders to quickly identify that they’re dealing with an ELF file.

Following the magic value, the next set of bytes in the e_ident array (indices 4 to 15) give more information about the type of the ELF file. Now, there’s no dedicated struct defined for these fields in /usr/include/elf.h, but having parsed the ELF Header myself a while ago, I can show you the corresponding struct representation for clarity.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

typedef struct

{

uint8_t fileIdn[4]; /* Magic bytes */

uint8_t ei_class; /* ELF Class (32/64 bits) */

uint8_t ei_data; /* Data encoding (LSB/MSB) */

uint8_t ei_version; /* ELF version */

uint8_t ei_osabi; /* OS ABI identification */

uint8_t ei_abiversion; /* OS ABI version */

uint8_t ei_pad[7]; /* Padding bytes */

} e_ident_t;

I have actually combined the whole 16-bytes into one structure for easier understanding.

fileIdn (indexes 0 to 3) is an array that represents teh magic value for identifying the file type

ei_class (4th byte) denotes whether the binary is for a 32-bit or 64-bit architecture. The class term used here is kind of cryptic as class can really mean anything. Now ei_class byte can have one of the two values:

ELFCLASS32which is equal to 1 and denotes 32-bit architectureELFCLASS64which is equal to 2 and denotes 64-bit architecture

ei_data (5th byte) indicates the endianness of binary.

ELFDATAlSB(equal to 1) indicates Little-endianELFDATAMSB(equal to 2) indicates Big-endian.

ei_version (6th byte) byte indicates the version of ELF specification used when creating the binary.

EV_CURRENT(equal to 1) is currently the only valid value forei_version

ei_osabi (7th byte) and ei_abiversion (8th byte) denote information regarding the application binary interface (ABI) and operating system (OS) for which the binary was compiled.

- If

ei_osabiis set to nonzero, it means that some ABI or OS-specific extension are used in the ELF file; this can change the meaning of some other fields in the binary or signal the presence of non-standard sections. The default value of 0 indicates that the binary targetsUNIX System V ABI. You can check the value from/usr/include/elf.h

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

#define EI_OSABI 7 /* OS ABI identification */

#define ELFOSABI_NONE 0 /* UNIX System V ABI */

#define ELFOSABI_SYSV 0 /* Alias. */

#define ELFOSABI_HPUX 1 /* HP-UX */

#define ELFOSABI_NETBSD 2 /* NetBSD. */

#define ELFOSABI_GNU 3 /* Object uses GNU ELF extensions. */

#define ELFOSABI_LINUX ELFOSABI_GNU /* Compatibility alias. */

#define ELFOSABI_SOLARIS 6 /* Sun Solaris. */

#define ELFOSABI_AIX 7 /* IBM AIX. */

#define ELFOSABI_IRIX 8 /* SGI Irix. */

#define ELFOSABI_FREEBSD 9 /* FreeBSD. */

#define ELFOSABI_TRU64 10 /* Compaq TRU64 UNIX. */

#define ELFOSABI_MODESTO 11 /* Novell Modesto. */

#define ELFOSABI_OPENBSD 12 /* OpenBSD. */

#define ELFOSABI_ARM_AEABI 64 /* ARM EABI */

#define ELFOSABI_ARM 97 /* ARM */

#define ELFOSABI_STANDALONE 255 /* Standalone (embedded) application */

ei_abiversionbyte denotes the specific version of the ABI indicated inei_osabibyte that the binary targets. It’s likely to be set to 0 because it’s not necessary to specify any version information when the defaultos_abiis used.

ei_pad field actually contains multiple bytes, namely, (indexes 9 through 15) in e_ident. All of these bytes are currently designated as padding; they are reserved for possible future use but currently set to zero.

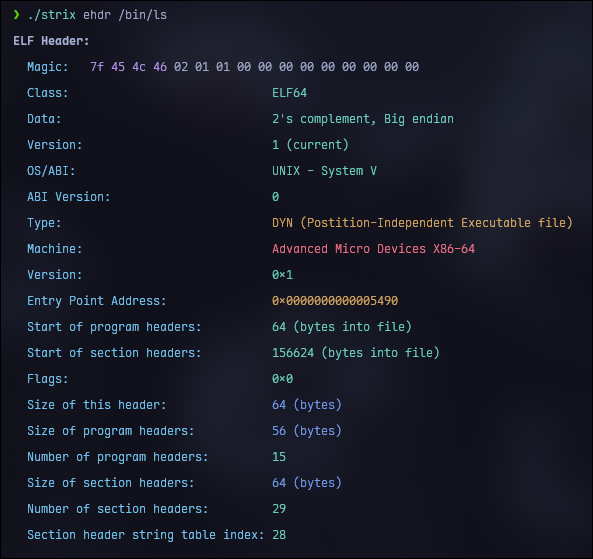

You can inspect the e_ident array of any ELF binary by using readelf or strix (modern alternative to readelf I’m working on) to view the binary’s header.

The e_type, e_machine and e_version Fields

So, after the e_ident array comes a series of multibyte integer fields.

e_type specifies the type of the binary. Most common values are:

EL_REL: Indicating relocatable object file.EL_EXEC: Indicating an executable binary.EL_DYN: Indicating a dynamic library, also called shared object file.

e_machine field specifies the architecture the binary is intended to run on. Now there are many possible values for this specfic field but the most common ones are:

EM_X86_64: Denotes 64-bit x86 binaries.EM_386: Denotes 32-bit x86 binaries.EM_ARM: Basically for ARM binaries.

e_version field serves the same role as ei_version byte in the e_ident array. Specifically, it again indicates the version of the ELF specification that was used when creating the binary. Now, as this is a 32-bit field, we can think there are numerous possible values, but in reality, the only possible value is 1 (EV_CURRENT) to indicate the version 1 of specification.

The e_entry Field

The e_entry field denotes the entry point of the binary. This is the virtual address at which the execution should start. This is actually where the interpreter (ld-linux-x86-64.so.2) will transfer control after it finishes loading the binary into virtual memory.

The e_phoff and e_shoff fields

Now, ELF binaries contain number of program headers and section headers. These headers need not be located at any particular offset in the binary file. The only data structure that can be assumed to be at a fixed location in an ELF file is the Executable header, which is always at the beginning.

To know where the program and section headers are located, you would consult the e_phoff and e_shoff fields in the executable header. These fields indicate the file offsets to the beginning of the program header table and the section header table. Here, table means an array of structures. Note that these are file offsets (not virtual addresses), meaning the number of bytes you should read into the file to reach them.

The e_flags field

The e_flags field provided room for flags specific to the architecture for which the binary is compiled. For instance, ARM binaries intended to run on embedded platforms can set ARM-specific flags in the e_flags field to indicate additional details about the interface they expect from the embedded operating system (file format conventions, stack organizations and so on). For binaries targeting x86 architecture, e_flags is typically set to zero.

The e_ehsize field

The e_ehsize field specifies the size of executable header in bytes. For 64-bit binaries, the executable header is always 64 bytes.

The e_*entsize and e_*num fields

We know that the e_phoff and e_shoff fields are file offsets where the program and section header tables begin. But for the programs like linker or loader (or another program handling ELF binary) to actually traverse these tables, additional information is needed.

Specifically, they need to know the size of the individual program or section headers in the tables, as well as the number of headers in each table.

This information is provided by:

e_phentsizeande_phnumfields for the program header table.e_shentsizeande_shnumfields for the section header table.

Note that:

- The

e_*entsizedenotes the size of an individual header. - The

e_*numdenotes the number of headers in each table.

The e_shstrndx field

The e_shstrndx field holds the index (within the section header table) to the section header that corresponds to the .shstrtab section.

.shstrtab is a dedicated string table used only for section names. It contains a sequence of null-terminated ASCII strings. Each section header’s sh_name field is not a literal name (you might have assumed XD); it is an offset into this .shstrtab string table. When parsing an ELF file:

- You would read

e_shstrndxfrom executable header. - Go to that index in the section header table to find the

.shstrtabsection header. - Use that header’s

sh_offsetandsh_sizeto load the.shstrtabbytes into memory. - For every section header, take its

sh_namevalue (an offset) and look it up inside the.shstrtabdata to get the actual section name.

This might feel incomplete right now since e_shstrndx points to a section header, and the way section headers work hasn’t been explained yet. That’s intentional. I’ll come back to the details of sh_name and the structure of section headers later, once the basics are introduced.

That’s it for the ELF header part. Next write-up is on program headers.